Ancient City Ruby Snake Case

Comparing mathematical, iterative, and recursive solutions

Last week I spoke at Ancient City Ruby Conference where the organizers encouraged people to participate in a Ruby programming challenge called Snake Case. I benchmarked a number of different ways to solve the challenge in Ruby and present the results here.

Here's the challenge:

THE ANCIENT CITY RUBY 2016 PROGRAMMING CHALLENGE

You've just arrived in sunny St. Augustine, and find yourself amazed by the visionary civic planning that would result in the area in which you now stand: a street grid exactly 10 blocks square.

You're in the northwest corner of this 10 by 10 block area, and would like to take a scenic walk to the southeast corner, while only ever moving south or east.

As you begin walking, you wonder to yourself, "how many different paths could I take from this northwest corner to the southeast corner?"

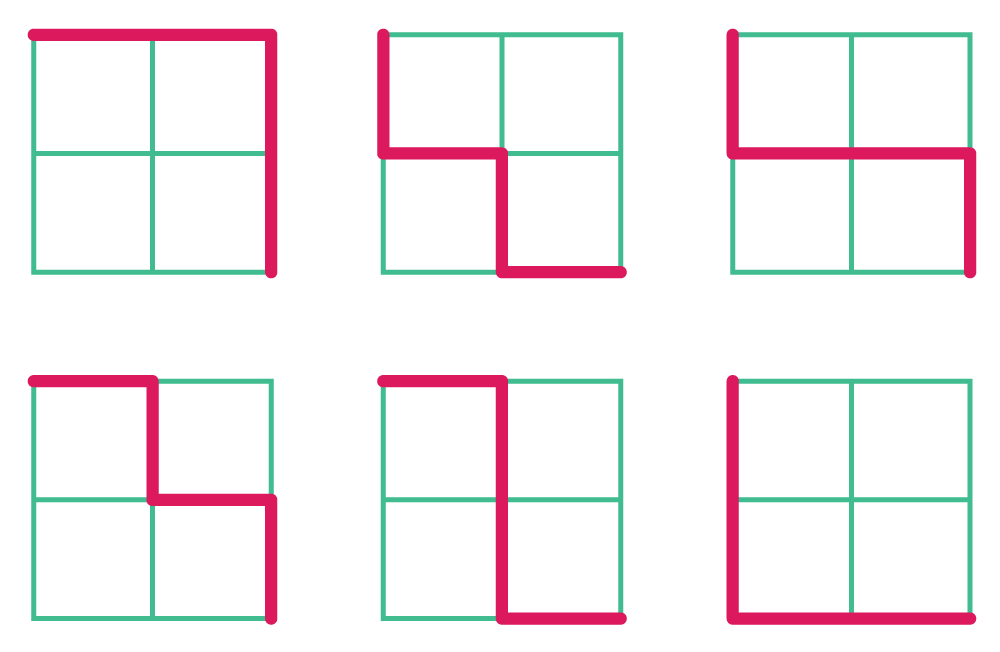

You quickly note that if the downtown area were only a 2 block by 2 block grid, there would be 6 distinct paths from one corner to the other:

It's worth nothing that the intent of the problem was to calculate the correct number of "optimal" paths along the blocks, so a meandering path does not count. Starting at the northwest corner of a 10x10 grid, there will be 20 moves in any valid path: 10 moves south and 10 moves east.

Recursion

How about a recursive solution? Consider that for any location h, w on the grid, there are either one or two incoming paths oriented in the south or west direction, one coming from neighbor h-1, w and the other coming from neighbor h, w-1.

This means that the solution for the given location is the sum of two subproblems: the number of paths arriving at location h-1, w plus the number of paths arriving at location h, w-1. In pseudocode:

path_count(h, w) = path_count(h-1, w) + path_count(h, w-1)

The exception to this rule is if either h or w are on the "edges", meaning the

value is 0. In this case, there's only 1 path that can reach these locations.

Now we have enough information to construct a recursive solution to the problem:

# recursive

def path_count(h, w)

return 1 if h == 0 || w == 0

path_count(h-1, w) + path_count(h, w-1)

end

The expected result for a 10x10 grid is 184,756.

path_count(10, 10)

# => 184756

This works! Let's consider some alternative approaches.

Binary and Binomial

Ray Hightower, who also spoke at ACR, recently published a nice writeup of a "brute force" solution in Ruby, C, and Go. Please check out his detailed explanation of both a mathematical and brute force solution in Ruby.

The mathematics approach is a factorial: given a 10x10 grid, we want to

construct 20 moves where 10 moves are "south" and 10 moves are "east". We could

represent this conceptually as a bit map, where the total number of bits is

20^2, or (h+w)**2 where h is the height and w is the width of the grid. It

turns out this can be represented as a binomial coefficient often expressed as:

Ray provided a nice LaTex-formatted description of the mathematics involved. Translated into a general Ruby function, this can be expressed in factorials.

# factorial

def path_count(h, w)

(h+w).downto(h+1).reduce(:*) / w.downto(1).reduce(:*)

end

This function gives the correct solution for 10x10: 184,756.

path_count(10, 10)

# => 184756

A "brute-force" solution counts up all the "1" bits in all possible combination of bits from 0 to 2^(h+w), or 2^20 in our case of a 10x10 grid.

Expressed in a general Ruby function:

# brute force

def path_count(h, w)

(0..(2**(h+w))).count { |x| x.to_s(2).chars.count("1") == n }

end

The total number of bits to explore is equal to 2**(h+w). We count how many of

those numbers, when expressed as binary with x.to_s(2) have 10 "1" bits.

Iteration

The recursive solution asks us to solve the problem backwards in a way: given the destination, figure out the solution by solving the problem for the nearest previous destinations and the ones that came before those and so on. What if we could "build up" to the solution instead? We can take an iterative approach in stead.

Imagine each corner or "node" of the grid can be represented as the number of paths leading to it. For a 5x5 grid, there are 6 nodes and each would have a value of 1, since there is only one way to get to those nodes.

1--1--1--1--1--1 # first row of a 5x5 grid

The second row gets interesting. Each node will be the sum of paths leading to

the nodes immediately north and west. So, the first node in the second row is

still just 1 since no paths lie to the west and the value of the node

immediately to the north is 1. The second node in the second row gets a value

of 2 since the node to the west is now 1 and the node to the north is also 1. Continuing on, this gives a second row of 1 2 3 4 5 6:

1--1--1--1--1--1

1--2--3--4--5--6

The third row:

1--1--1--1--1--1

1--2--3--4--5--6

1--3--6--10-15-21

And so on... The number of paths for a given grid would simply be the value of the last node in the last row. Let's implement this in Ruby:

# iterative

def path_count(h, w)

row = [1] * (w+1) # first row of "1s"

h.times do

row = row.reduce([]) { |acc, p| acc << (p + acc.last.to_i) }

end

row.last

end

The reduce expression generates a row from the previous one and the values of

each previous member of the current row. The function returns the last member of

the last row.

Since I gave a talk about Enumerator at Ancient City I decided it would only

be appropriate if I solved the Snake Case challenge using an Enumerator. We

can extract an Enumerator from the iterative solution to represent a function that generates each row of the grid:

def grid(h, w)

return to_enum(:grid, h, w) unless block_given?

row = [1] * (w+1)

yield row

h.times do

row = row.reduce([]) { |acc, p| acc << (p + acc.last.to_i) }

yield row

end

end

Two key changes have been made. We've inserted yield statements to allow the

caller to receive each row of the grid as it is generated. We also "enumeratorize" our iterative function by converting the behavior of the function into an Enumerator when no block is given in the first line.

Calling grid(10, 10) returns an Enumerator:

grid(10, 10)

# => #<Enumerator: ...>

Calling to_a on our Enumerator creates each "node" value:

grid(10, 10).to_a

# => [[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

# [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11],

# [1, 3, 6, 10, 15, 21, 28, 36, 45, 55, 66],

# [1, 4, 10, 20, 35, 56, 84, 120, 165, 220, 286],

# [1, 5, 15, 35, 70, 126, 210, 330, 495, 715, 1001],

# [1, 6, 21, 56, 126, 252, 462, 792, 1287, 2002, 3003],

# [1, 7, 28, 84, 210, 462, 924, 1716, 3003, 5005, 8008],

# [1, 8, 36, 120, 330, 792, 1716, 3432, 6435, 11440, 19448],

# [1, 9, 45, 165, 495, 1287, 3003, 6435, 12870, 24310, 43758],

# [1, 10, 55, 220, 715, 2002, 5005, 11440, 24310, 48620, 92378],

# [1, 11, 66, 286, 1001, 3003, 8008, 19448, 43758, 92378, 184756]]

Notice the last value of the last row is the correct answer to our path count challenge.

For our revised path_count method, we simply want to retrieve the last member of the last row:

# enumeartive

def path_count(h, w)

grid(h, w).drop(h-1).last.last

end

It's worth noting that the nodes of this grid follow the pattern of Pascal's Triangle expanding from the northwest corner. Pascal's Triangle is well suited for an Enumerator function as I've written about previously.

Tradeoffs

We've described a number of ways to solve Snake Case and each comes with tradeoffs.

In terms of readability, I would personally place the solutions in the following order from most to least readable:

- Recursive

- Iterative

- Brute force

- Factorial

At least for me, the recursive solution is the easiest to wrap my head around and most readable result. It's easy to see from the recursive implementation how the problem may be divided into smaller sub-problems. The others require some deeper visualization and/or mathematical understanding to "grok" I feel. The factorial expression seems farthest removed conceptually from the description of the problem. In other words, it's most at odds with my intuition, but I'm also not a mathematician so am less inclined to think in those terms.

How do they compare performance-wise? With benchmark-ips we can compare the

iterations/second and share the results.

Here's a file that defines each of the approaches we've described in separate modules and benchmarks the performance for calculating the result for a 10x10 grid. (Full source)

Running on my mid-2014 MacBook Pro with MRI ruby-2.3:

require "benchmark/ips"

Benchmark.ips do |x|

x.report("snake case factorial") do

SnakeCase::Factorial.path_count(10, 10)

end

x.report("snake case brute force") do

SnakeCase::Bruteforce.path_count(10, 10)

end

x.report("snake case recursive") do

SnakeCase::Recursive.path_count(10, 10)

end

x.report("snake case iterative") do

SnakeCase::Iterative.path_count(10, 10)

end

x.report("snake case enumerative") do

SnakeCase::Enumerative.path_count(10, 10)

end

x.compare!

end

# $ SHARE=1 ruby code/snake_case.rb

# Calculating -------------------------------------

# snake case factorial 34.658k i/100ms

# snake case brute force

# 1.000 i/100ms

# snake case recursive 5.000 i/100ms

# snake case iterative 4.920k i/100ms

# snake case enumerative

# 4.109k i/100ms

# -------------------------------------------------

# snake case factorial 456.100k (± 7.8%) i/s - 2.287M

# snake case brute force

# 0.325 (± 0.0%) i/s - 2.000 in 6.161730s

# snake case recursive 50.084 (±10.0%) i/s - 250.000

# snake case iterative 52.616k (± 5.3%) i/s - 265.680k

# snake case enumerative

# 42.875k (± 7.1%) i/s - 213.668k

#

# Comparison:

# snake case factorial: 456100.0 i/s

# snake case iterative: 52615.9 i/s - 8.67x slower

# snake case enumerative: 42874.6 i/s - 10.64x slower

# snake case recursive: 50.1 i/s - 9106.72x slower

# snake case brute force: 0.3 i/s - 1405090.92x slower

#

# Shared at: https://benchmark.fyi/f

The factorial solution is orders of magnitude faster than the others. The iterative (and relatively similar enumerative) examples are only about ~10x slower than the factorial version while the recursive solution is almost 10,000x slower. The brute force solution is over a million-times slower. Even though the standard deviation in some of the results was fairly large, the differences across strategies appear conclusive.

The maintainer of benchmark-ips, Evan Phoenix, added the ability to share benchmark results online. You can see the results for this test on benchmark.fyi. The full source code is also on GitHub.

And the winner is...

All of the above!

This serves as a good illustration of how there's often no single "best" way to solve a problem with considering the circumstance. In a situation where performance matters, the mathematical approach has a clear advantage, but sacrifices readability. I might be inclined to choose the iterative or recursive approach in situations where performance isn't the key concern.

Given my preference for Enumerable, I personally love the enumerative approach, but, as I discussed at Ancient City Ruby, I doubt most would agree.