Pascal's Triangle with Ruby's Enumerator

Pascals' Triangle as an Enumerable Sequence with Ruby Enumerator

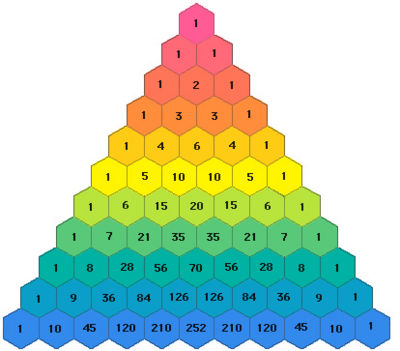

Pascal's Triangle is a fun sequence. Here's what it looks like:

It represents a "triangular array of the binomial coefficients". Each row contains an increases in size and contains numbers which can be derived by adding adjacent members of the previous row.

We can model this in Ruby as an array of arrays. The first array member is [1]. Each successive array (or "row") will increase in size, and each array member will be the sum of the member at the same index n in the k-1 row, where k is the current row, and the n-1 member in the k-1 row or 0. In other words, add the number above and the number above to the left (or zero) to get the current number. We can express the first five rows as follows:

[

[1],

[1, 1],

[1, 2, 1],

[1, 3, 3, 1],

[1, 4, 6, 4, 1]

]

Let's solve this with Ruby. While there are a number of approaches to generating Pascal's Triangle, including both recursive and iterative solutions, we'll explore an approach to treating this as an enumerable.

Starting with the first row, [1], we can write a Ruby method that will generate the next row [1, 1]. Let's write this in a way so it will be possible to generate any row k from row k-1. Here's what the usage of this method will look like:

pascal_row([1])

=> [1, 1]

pascal_row([1, 3, 3, 1])

=> [1, 4, 6, 4, 1]

We'll use Test-Driven Development to validate our implementation starting with a few assertions to ensure the first several rows are returned as expected.

require 'minitest/autorun'

def pascals_row(row)

# yo no se

end

class TestPascalsTriangle < Minitest::Test

def test_pascals_row

assert_equal [1, 1], pascals_row([1])

assert_equal [1, 2, 1], pascals_row([1, 1])

assert_equal [1, 3, 3, 1], pascals_row([1, 2, 1])

assert_equal [1, 4, 6, 4, 1], pascals_row([1, 3, 3, 1])

assert_equal [1, 5, 10, 10, 5, 1], pascals_row([1, 4, 6, 4, 1])

end

end

Our failing test run will look something like this:

$ ruby pascals_triangle_test.rb

Run options: --seed 45117

# Running:

F

Finished in 0.001035s, 966.0380 runs/s, 966.0380 assertions/s.

1) Failure:

TestPascalsTriangle#test_pascals_row [code/pascals_row_test.rb:8]:

Expected: [1, 1]

Actual: nil

1 runs, 1 assertions, 1 failures, 0 errors, 0 skips

To extract a general method, let's deconstruct a single row, the fifth: [1, 4, 6, 4, 1]. Each member is the sum of n and n-1 from the previous row, [1, 3, 3, 1]. We substitute zero when n or n-1 is missing. Therefore, we can rewrite the fifth row as

[(0 + 1), (1 + 3), (3 + 3), (3 + 1), (1 + 0)]

=> [1, 4, 6, 4, 1]

We can also represent this as a nested array of number pairs then collect the sum of each pair like so:

[[0, 1], [1, 3], [3, 3], [3, 1], [1, 0]].collect { |a, b| a + b }

=> [1, 4, 6, 4, 1]

Looking closely at the pairs, taking just first members of each pair form the array we get [0, 1, 3, 3, 1]. The second members of each pair are [1, 3, 3, 1, 0]. Written differently, the groups are ([0] + [1, 3, 3, 1]) and ([1, 3, 3, 1] + [0]). In each we see the members of row four, [1, 3, 3, 1] augmented by prepending zero or appending zero respectively.

Getting the nested array pairs from these groups is perfect for the Enumerable#zip method: zip groups members of given arrays by position. Therefore, we can "zip" [0, 1, 3, 3, 1] with [1, 3, 3, 1, 0] to produce [[0, 1], [1, 3], [3, 3], [3, 1], [1, 0]]:

[0, 1, 3, 3, 1].zip([1, 3, 3, 1, 0])

=> [[0, 1], [1, 3], [3, 3], [3, 1], [1, 0]]

Let's extract a variable to represent row four:

row = [1, 3, 3, 1]

([0] + row).zip(row + [0])

=> [[0, 1], [1, 3], [3, 3], [3, 1], [1, 0]]

Putting it altogether, we can now produce the fifth row from the fourth:

row = [1, 3, 3, 1]

([0] + row).zip(row + [0]).collect { |a, b| a + b }

=> [1, 4, 6, 4, 1]

Let's confirm this expression works with for other row conversions:

row = [1]

([0] + row).zip(row + [0]).collect { |a, b| a + b }

=> [1, 1]

row = [1, 1]

([0] + row).zip(row + [0]).collect { |a, b| a + b }

=> [1, 2, 1]

row = [1, 2, 1]

([0] + row).zip(row + [0]).collect { |a, b| a + b }

=> [1, 3, 3, 1]

Yes! We now have the implementation for our method to produce any row for Pascal's Triangle given the preceding row:

def pascal_row(row)

([0] + row).zip(row + [0]).collect { |a, b| a + b }

end

Plugging in this implementation...

require 'minitest/autorun'

def pascals_row(row)

([0] + row).zip(row + [0]).collect { |a, b| a + b }

end

class TestPascalsTriangle < Minitest::Test

def test_pascals_row

assert_equal [1, 1], pascals_row([1])

assert_equal [1, 2, 1], pascals_row([1, 1])

assert_equal [1, 3, 3, 1], pascals_row([1, 2, 1])

assert_equal [1, 4, 6, 4, 1], pascals_row([1, 3, 3, 1])

assert_equal [1, 5, 10, 10, 5, 1], pascals_row([1, 4, 6, 4, 1])

end

end

... we get passing tests

$ ruby code/pascals_row_test.rb

Run options: --seed 61039

# Running:

.

Finished in 0.001020s, 980.6882 runs/s, 4903.4412 assertions/s.

1 runs, 5 assertions, 0 failures, 0 errors, 0 skips

In Sequence

Now that we have a method to convert one row to its successor, we have a nice building block for an infinite sequence. We can call pascals_row repeatedly to generate the triangle rows infinitely. I previously wrote about creating infinite sequences in Ruby with Enumerator and we'll apply this approach here.

We'd like to be able to call a method and enumerate the rows representing Pascal's Triangle as we would for an array. Since we'll be using Enumerator, which exposes the Enumerable api, we can use external enumeration with Enumerator#next to extract rows in succession. Let's rewrite our previous test to demonstrate:

require 'minitest/autorun'

def pascals_triangle

# Enumerator, please

end

def pascals_row(row)

([0] + row).zip(row + [0]).collect { |a, b| a + b }

end

class TestPascalsTriangle < Minitest::Test

def test_pascals_triangle

rows = pascals_triangle

assert_equal [1], rows.next

assert_equal [1, 1], rows.next

assert_equal [1, 2, 1], rows.next

assert_equal [1, 3, 3, 1], rows.next

assert_equal [1, 4, 6, 4, 1], rows.next

assert_equal [1, 5, 10, 10, 5, 1], rows.next

end

end

With no implementation, the test fails on calling next:

$ ruby pascals_triangle_test.rb

Run options: --seed 62081

# Running:

E

Finished in 0.000949s, 1053.4832 runs/s, 0.0000 assertions/s.

1) Error:

TestPascalsTriangle#test_pascals_rows:

NoMethodError: undefined method `next' for nil:NilClass

code/pascals_row_test.rb:14:in `test_pascals_rows'

1 runs, 0 assertions, 0 failures, 1 errors, 0 skips

Our enumerator needs to call the pascals_row method repeatedly with the

previous result. We'll maintain the current row as current, pass this as the

arg to pascals_row, replace it with the result and repeat in a loop. Returning the

Enumerator from the method will allow the caller to control how it's

enumerated.

Here's what the implementation could look like:

current = [1]

Enumerator.new do |y|

loop do

y << current

current = pascals_row(current)

end

end

Let's plug this into our method and rerun:

require 'minitest/autorun'

def pascals_triangle(row = [1])

current = row

Enumerator.new do |y|

loop do

y << current

current = pascals_row(current)

end

end

end

def pascals_row(row)

([0] + row).zip(row + [0]).collect { |a, b| a + b }

end

class TestPascalsTriangle < Minitest::Test

def test_pascals_rows

rows = pascals_triangle

assert_equal [1], rows.next

assert_equal [1, 1], rows.next

assert_equal [1, 2, 1], rows.next

assert_equal [1, 3, 3, 1], rows.next

assert_equal [1, 4, 6, 4, 1], rows.next

assert_equal [1, 5, 10, 10, 5, 1], rows.next

end

end

The exciting thing about this implementation is we can treat our sequence like a collection and call enumerable methods. We can also chain enumerable methods like Enumerator#with_index and Enumerator#each to print a "pretty" triangle of each row with its row number.

pascals_triangle.with_index(1).take(10).each do |row, i|

puts "%d:%#{20+(row.inspect.length/2)}s" % [i, row.inspect]

end

1: [1]

2: [1, 1]

3: [1, 2, 1]

4: [1, 3, 3, 1]

5: [1, 4, 6, 4, 1]

6: [1, 5, 10, 10, 5, 1]

7: [1, 6, 15, 20, 15, 6, 1]

8: [1, 7, 21, 35, 35, 21, 7, 1]

9: [1, 8, 28, 56, 70, 56, 28, 8, 1]

10: [1, 9, 36, 84, 126, 126, 84, 36, 9, 1]

=>

[[[1], 1],

[[1, 1], 2],

[[1, 2, 1], 3],

[[1, 3, 3, 1], 4],

[[1, 4, 6, 4, 1], 5],

[[1, 5, 10, 10, 5, 1], 6],

[[1, 6, 15, 20, 15, 6, 1], 7],

[[1, 7, 21, 35, 35, 21, 7, 1], 8],

[[1, 8, 28, 56, 70, 56, 28, 8, 1], 9],

[[1, 9, 36, 84, 126, 126, 84, 36, 9, 1], 10]]

Notice the return value combines the each row with its index, an interesting outcome of how enumerator chains can augment the enumerated values.

We can also take advantage of Enumerator#lazy to operate on rows without relying on eager evaluation. Here we use a lazy enumerator chain to demonstrate that the sum of numbers in each row is 2^n:

pascals_triangle.lazy.map { |row| Math.log(row.reduce(:+), 2) }.take_while { |n| n < 9 }.force

=> [0.0, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0]

Enumerators allow us to provide an enumerable interface to generated data in much the same way we do for collections. Try test-driving an enumerable implementation of other sequences on your own.